Japanese art represents the soul of a nation steeped in rich history, profound cultural values, and an intimate relationship with nature.

It spans millennia and encompasses various art forms, such as calligraphy, painting, pottery, textiles, sculpture, and architecture.

Through its evolution, Japanese art has served as a visual and spiritual language that reflects the nation’s ethos, spirituality, and appreciation for beauty and impermanence.

Drawing from historical periods and traditional symbolism, this article explores what Japanese art represents.

The Historical Context of Japanese Art

Early Foundations: Jomon, Yayoi, and Kofun Periods

The roots of Japanese art trace back to the Jomon period (10,500–300 BCE), characterized by cord-marked pottery and clay figurines known as dogū.

These figurines, often with exaggerated female features, symbolized fertility and spiritual beliefs, demonstrating the intimate connection between art and life.

Pottery from this period reveals the aesthetic sophistication of early hunter-gatherers.

The Yayoi period (300 BCE–250 CE) introduced technological advancements like wheel-thrown pottery and bronze tools. Art from this era reflects an increasing emphasis on functionality while retaining decorative beauty.

By the Kofun period (250–538 CE), burial mounds (kofun) adorned with clay sculptures (haniwa) became significant, symbolizing the growing power of the elite and their spiritual beliefs.

The Influence of Buddhism: Asuka and Nara Periods

Buddhism entered Japan during the Asuka period (538–710 CE) and profoundly influenced Japanese art. Religious sculptures, temple architecture, and paintings reflected Buddhist philosophies.

The construction of Hōryū-ji, one of the oldest wooden temples in the world, stands as a testament to this era’s artistry.

The Nara period (710–784 CE) further solidified Buddhist themes in art.

Clay figures and lacquered statues of Buddhist deities became popular, while scroll paintings depicting religious narratives flourished.

These works symbolized the spiritual aspirations of a society deeply influenced by Buddhism.

Cultural Flourishing: Heian Period

The Heian period (794–1185 CE) marked a golden age for Japanese art.

As the imperial court sought to balance political power with spiritual life, Pure Land Buddhism introduced the construction of Amida halls.

These halls, such as the Phoenix Hall at Byōdō-in, merged religious devotion with architectural beauty.

Art during this period also embraced secular themes. He illustrated handscrolls (emaki), such as the Genji Monogatari Emaki, blended narrative storytelling with intricate visuals, depicting courtly life and romantic ideals.

The Yamato-e style, characterized by vibrant colours and detailed landscapes, emerged as a uniquely Japanese form of painting.

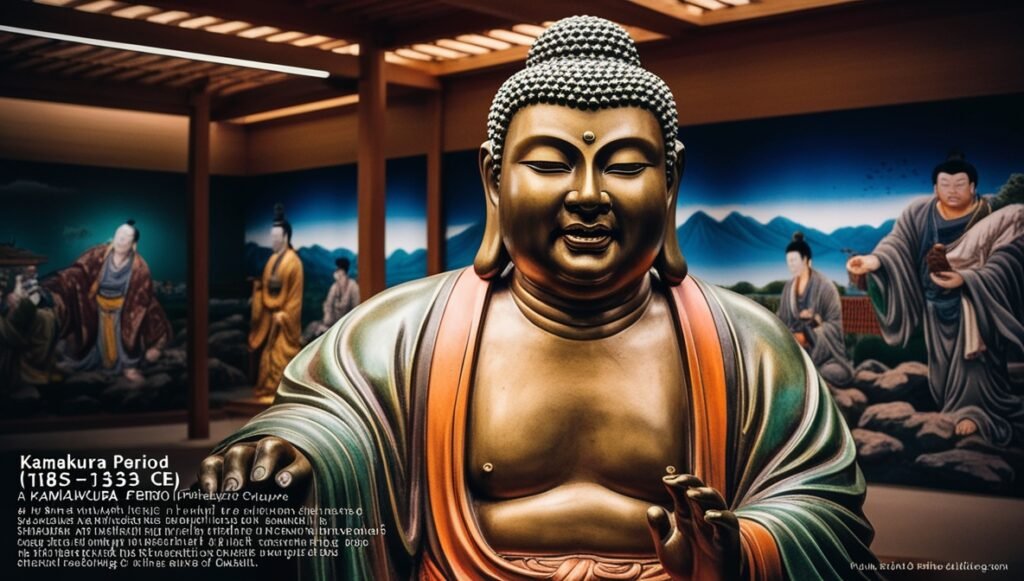

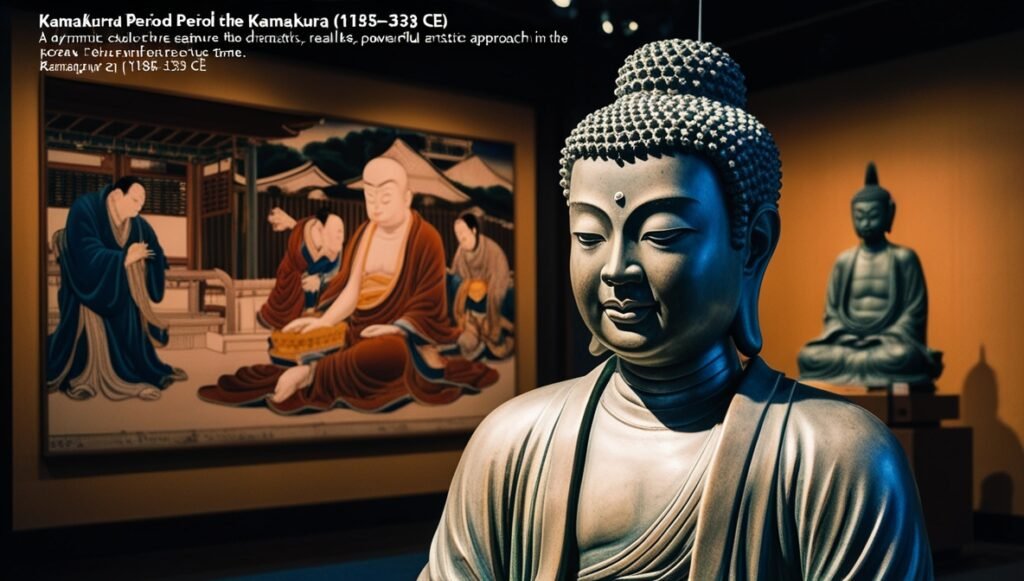

Realism and Popularization: Kamakura Period

With the rise of the warrior class in the Kamakura period (1185–1333 CE), art became more realistic and accessible.

Sculptors like Unkei and Kaikei mastered dynamic and lifelike representations of Buddhist figures, while narrative paintings like the Heiji Monogatari Emaki illustrated dramatic historical events.

This period also saw the popularization of illustrated texts, combining visual and written elements to make religious and historical stories accessible to commoners.

The focus shifted toward art that resonated with broader audiences.

Zen and Minimalism: Muromachi Period

The Muromachi period (1336–1573 CE) saw the influence of Zen Buddhism, emphasizing simplicity and meditative aesthetics.

Monochrome ink paintings (sumi-e), inspired by Chinese styles, depicted serene landscapes and spiritual themes.

Zen gardens, like those at Ryōan-ji, embodied the principles of harmony and introspection, representing a microcosm of the natural world.

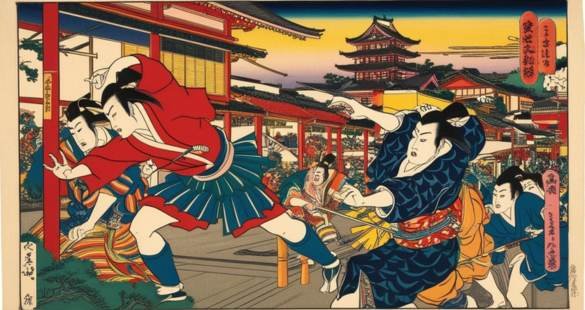

Opulence and Individuality: Edo Period

The Edo period (1603–1868 CE) brought a cultural explosion, with art becoming more diverse and accessible.

Ukiyo-e woodblock prints captured scenes of daily life, Kabuki actors, and landscapes, making art a commodity for the masses.

Masters like Hokusai and Hiroshige immortalized nature and urban life through bold, colorful designs.

Meanwhile, architecture, textiles, and pottery flourished.

The Katsura Imperial Villa exemplified classical Japanese design, blending natural elements with innovative structures.

This era highlighted the interplay between tradition and innovation, reflecting the growing complexity of Japanese society.

Themes and Symbolism in Japanese Art

Nature as a Central Motif

Nature is a recurring theme in Japanese art, symbolizing harmony, beauty, and the transient nature of life. also geometric patterns, mythical creatures, and spiritual symbols.

Cherry blossoms (sakura), with their fleeting bloom, epitomize the impermanence of existence.

Pine trees, bamboo, and plum blossoms signify strength, resilience, and renewal.

Animals like the red-crowned crane represent longevity and good fortune, while koi fish symbolize perseverance and courage.

These motifs underscore a deep respect for the natural world and its cycles.

Spiritual and Cultural Symbols

Japanese art is rich with spiritual and cultural symbols.

The Torii gate, marking the boundary between the sacred and the profane, often appears in paintings and sculptures.

The circular brushstroke in calligraphy embodies enlightenment and the interconnectedness of life.

Buddhist icons, from statues to mandalas, represent spiritual journeys and universal truths.

Mythical creatures like dragons and phoenixes symbolize power, wisdom, and transformation, blending spiritual meaning with artistic grandeur.

Aesthetic Principles

Japanese art embodies the aesthetic principles of wabi-sabi—the beauty of imperfection and impermanence.

Whether in the weathered surface of a tea bowl or the asymmetry of a Zen garden, this philosophy encourages a profound appreciation for simplicity and authenticity.

The principle of ma (negative space) also plays a crucial role, emphasizing balance and allowing viewers to engage with the artwork’s emptiness as much as its form.

What Japanese Art Represents

At its core, Japanese art represents:

- Cultural Identity: A preservation of traditions and values through visual storytelling.

- Spirituality: A medium for exploring and expressing connections with the divine and the self.

- Nature’s Essence: A celebration of the natural world and its transient beauty.

- Historical Narratives: A chronicle of societal shifts from ancient beliefs to modern innovations.

- Aesthetic Philosophy: A commitment to harmony, simplicity, and the art of imperfection.

Conclusion

Japanese art is a timeless dialogue between tradition and innovation, the physical and spiritual, and the ephemeral and eternal.

From the intricate brushstrokes of a calligrapher to the sweeping landscapes of ukiyo-e prints, every piece tells a story, invites introspection, and bridges the past with the present.

It is not just an art form but a philosophy, an identity, and a celebration of life in all its fleeting beauty.